Tenaya

September

2013

Part Four

Sailing Canoes in Ninigo

Papua New Guinea

| |

| HOME |

| About Tenaya |

| About Us |

| Latest Update |

| Logs from Current Year |

| Logs from Previous Years |

| Katie's View |

| Route Map |

| Links |

| Contact Us |

![]()

September 30, 2013

Squinting to find the pass through the barrier reef at Ninigo Atoll, I see a brilliant blue rectangle slide south inside the lagoon. As we creep towards the anchorage another one glides by. Sailing canoes!

After we drop the hook we are sitting in the cockpit with our welcoming crew telling stories and a wa sails by. "That's my brother," Thomas says. Joseph waves and is soon gone.

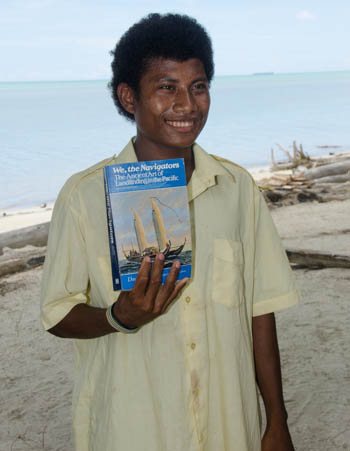

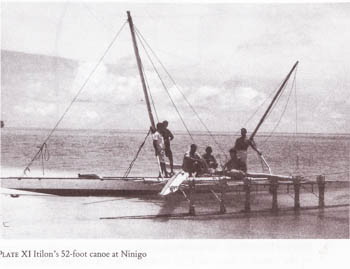

David Lewis put Ninigo on the map, literally, in his informative book, We, the Navigators. He studied the construction, sailing and navigational techniques from several areas across the Pacific including Ninigo. Lewis befriended Itilon here and sailed with him on his 52' sailing canoe. Pictures are included in his book.

We tell Thomas about the sailaus, sailing canoes in the Louisiades, and ask him if he has seen Lewis' book. He has not so I fetch our copy. Westley get a hold of it and doesn't put it down. The others read over his shoulder. They all know the boat in the picture. Westley points out the island where Itilon lived and says some of his family live here on Mal.

Thomas says he is building his own sailing canoe, called a wa in Seimat, the local language. He is about to put the hull on the keel. Would we like to watch and take photos? Certainly!

"Do you make many was?" Jim asks.

"No. I have to wait for the right type of driftwood to wash up on the beach."

"How often does one come?"

"About every two years. Sometimes longer. So I wait."

After our tour of Puhipi village, Thomas, his brother Clement, his son Richard, and his wife Elizabeth get started putting the wa together.

The keel has already been shaped from wood grown on the island and hard wooden dowels have been pounded into it. The dowels poke through holes cut in foam that stretches along the narrow top of the hull.

Corresponding holes have already been drilled into the bottom of the hull which rests next to the keel. The hull is called hunahun and is the very hard, reddish wood that washes up on shore. Planks are cut from the driftwood log and then planed until smooth. Thomas uses tools from his great grandfather. None are electric.

Thomas and Richard lift up the hull and align it as Thomas stands at one end. Elizabeth makes sure the first holes line up and then they slowly set the hull down. Lines drawn with pencils on both the keel and hull mark the location of the dowels.

Once the hull is resting on the keel Richard and Clement force the hull and keel together using vices.

When the hull has been attached to the keel and the dowels are no longer visible, the pencil marks meet. This is where Richard and Clement drill narrow holes to pound in wooden nails called hasa. Hasa can last more than 10 years. A frisbee holds dozens of tapered hasa.

Once Thomas' wa is finished it will look something like Joseph's.

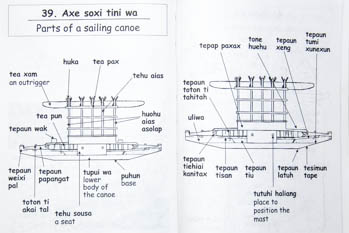

Chris Omen, headmaster of Mal/Lau Primary School, gave us a copy of a Seimat-English picture dictionary. This picture is taken from that. It appears there are not English words for all of the intricate parts of a wa!

A wa can sail up to 15 knots. The outrigger is always on the winward side and to tack or gybe the line opposite the mast is freed, the sail is spun around, and the line is reattached.

One day we go to the far end of the island where we meet Leopard. His father was pictured on Itilon's sailing canoe in the book We, the Navigators. He shows us the large white sailing canoe his brother recently built. It sits on the beach and kids are playing on and around it.

We meet Lisha and Calbert. Itilon was their grandfather. Later Lisha introduces us to her mother, Robin, Itilon's daughter. They are all very interested in seeing the book. We tell them we have already promised it to Westley but will print copies of photos from the book for them. Chris from the primary school says he was able to thumb through a copy once but does have one. We get his address in hopes we can order one or two copies for the school. They should have this book!

Thomas, Elizabeth and Richard guide us through the bush to Piakahu. Over fallen logs and around coconut sized holes we walk along the wide overgrown trail. Crabs the size of soup bowls steal about like little thieves, running then stopping to look around as if they are guilty of something.

Westley is thrilled to receive the book. He shows it to Sheddy who is also a grandchild of Itilon's. Westley says he is very happy because he wants to learn the currents, which are illustrated well, so he will know where to look when someone goes missing in their canoe.

Archaeological evidence shows humans reached New Guinea 60,000 years ago and 30,000 years ago moved on to the Bismarck and Solomon Islands. About 3,000 years ago the migration east continued, reaching Vanuatu and Fiji. By 800-1700 years ago they had reached the Cook Islands, French Polynesia and Easter Island. Many experts believe the Polynesians continued east and reached South America. While they are still looking for more proof, Dr. Lisa Matisoo-Smith, Dept. of Anatomy, University of Otago, told us over tequila on board Tenaya in Kavieng that “there was no sign on Easter Island saying ‘Stop here, no more islands, only the mainland!”

Lisa gave us a thumb drive with several papers relating to the westward migration of the Pacific including one she coauthored, Untangling Oceanic settlement: the edge of the knowable. Also on the stick was Voyaging by canoe and computer: experiments in the settlement of the Pacific Ocean. All intelligent text in this section is taken from these.

Some of the questions about this migration are: 1) Was discovery one-way or two-way navigation? 2) Was navigation a matter of chance or technological competence? 3) How many explorers may have survived or died at sea? Prehistorians have had many theories about the routes and methods, often looking for the shortest routes but without considering the ease of travel. Geoffrey Irwin, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Auckland, and also a yachtie, realized from his own experience that wind and currents were much more important. Other researchers have shown that the major voyages could not have occurred by drift alone and required a knowledge of navigation.

Irwin, along with Simon Bickler, Dept of Anthropology, University of Auckland, and Philip Quirke Dept. of Mathematics, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Auckland created a computer program using wind and current information, the probability of storms and the distance different height islands could be seen. This program plotted the probable courses of sailing canoes using different strategies, and their chances of finding a new island and then the possibility of a safe return. The program showed that a strategy of directed navigation and returning by latitude sailing had a reasonable chance of finding new islands and a very good chance of a safe return. Irwin, Bickler and Quirke conclude that the explorers were concerned for their safety, their actions were deliberate and rational, and they did not have a mistaken view of their oceanic world as they spread swiftly across it. “The settlement of the Pacific was undoubtedly a most remarkable episode in human prehistory.”

The people living in Ninigo are descendents of these early sailors and navigators. Sailing is still very much a part of their lives. Indeed, it is the preferred way of getting around the atoll.

Itilon's canoe was large so it had two sails. All those we see are small and only have one. It appears they are assembled much the same way they were nearly 50 years ago and probably for hundreds of years before that.

While we visit our new friends at Piakahu three sailing canoes appear on the horizon and grow larger as they approach. They are coming here! Jim takes about a million pictures of them arriving and departing. Joseph and his daughter, Judy, are on one and we aren't sure who the others are. Plans had been to have a race that day with Tenaya being a mark, but the wind was light so it was cancelled. We are happy they still went sailing and we could watch. Kemulik wanen! Thank you very much.

Go to October 2013 Part One- Passage from Papua New Guinea to Palau Diverted to Jayapura, Indonesia

Go back to September 2013 Part Three - Mal Island, Ninigo Atoll, Papua New Guinea